AN AMERICAN STORY, “Fujiwara”

By Korine Fujiwara, violist

“Watashi no chīsai akambō dōzo, yoku kiite kudasai”

(My little children, please listen carefully)

This phrase was the beginning of every bedtime story told to me by my father Karlo Fujiwara, a tradition passed down by my grandfather Rinney Fujiwara to my father, from my great-grandfather Fujiwara Sunejiro, and from his father before him (my great-great-grandfather) Fujiwara no Sadajiro.

It’s hard to know where to begin in the telling of ancestral stories. My Ancestors come from Japan, Norway, Scotland, Wales, and Germany, but the stories I am most familiar with and therefore the tale I tell in An American Story is that of my Japanese grandfather, Rinney “Rine” Fujiwara.

Incidentally, having a middle name is not a Japanese tradition, so let’s begin with the story of how my grandfather received his middle name, as relayed by my father.

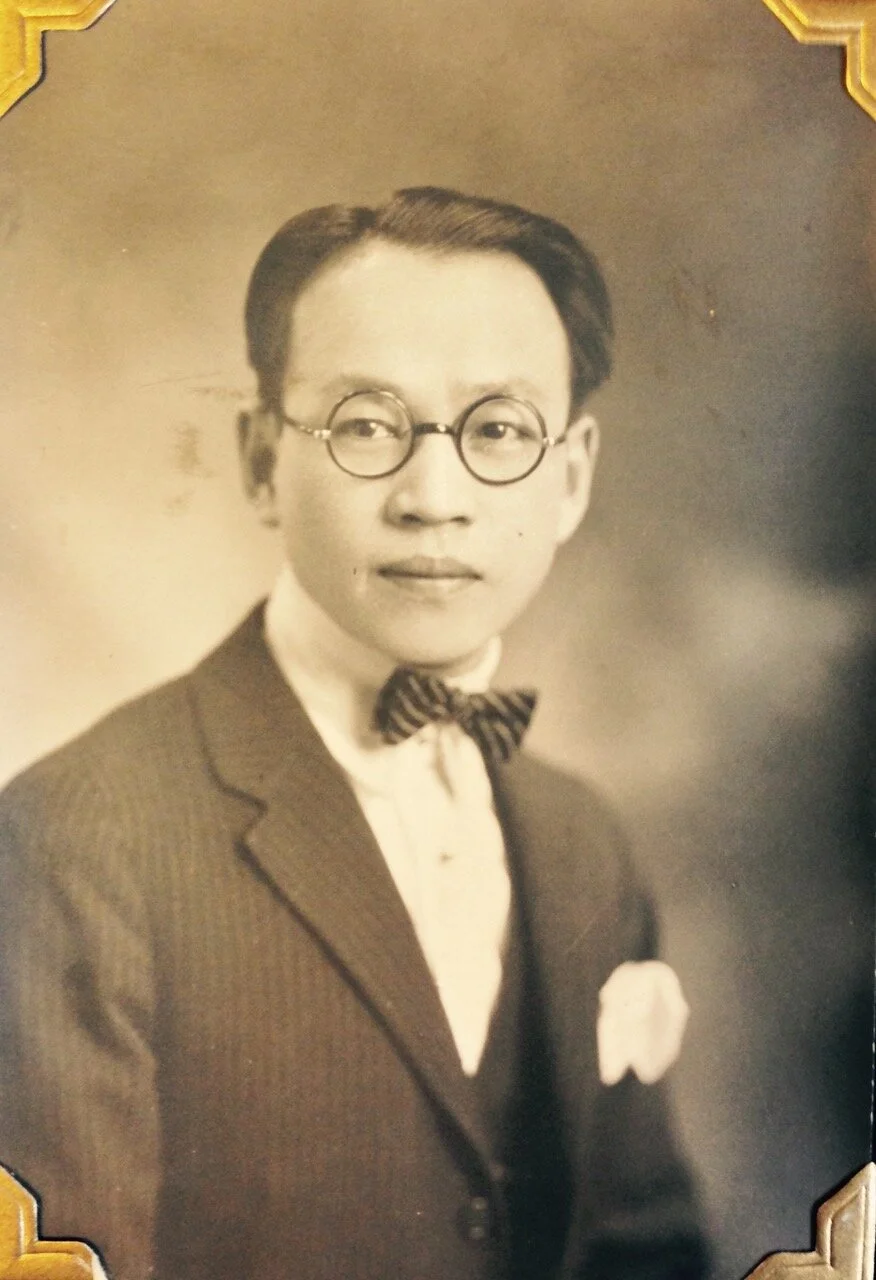

When your grandfather came to the US just after the first decade of the 1900’s, his name in Romaji was Fujihara, Rine. When the immigration officials asked him, “Okay, what is your middle name?” the 13 year old looked at them bewildered and answered, “Fujihara, Rine, is.” “No, no, what is your WHOLE name?” they continued to ask. “What is your family name?” “Ah, Fujihara, famirry namae is.” the young teenager replied. “What is the next name?” they asked. “Rine” he politely replied. “Next name?” and he printed R-I-N-E and said, “Onry, prease.” So the immigration officials wrote Rinney Rine Fujiwara.

And that’s how my grandfather got his middle name.

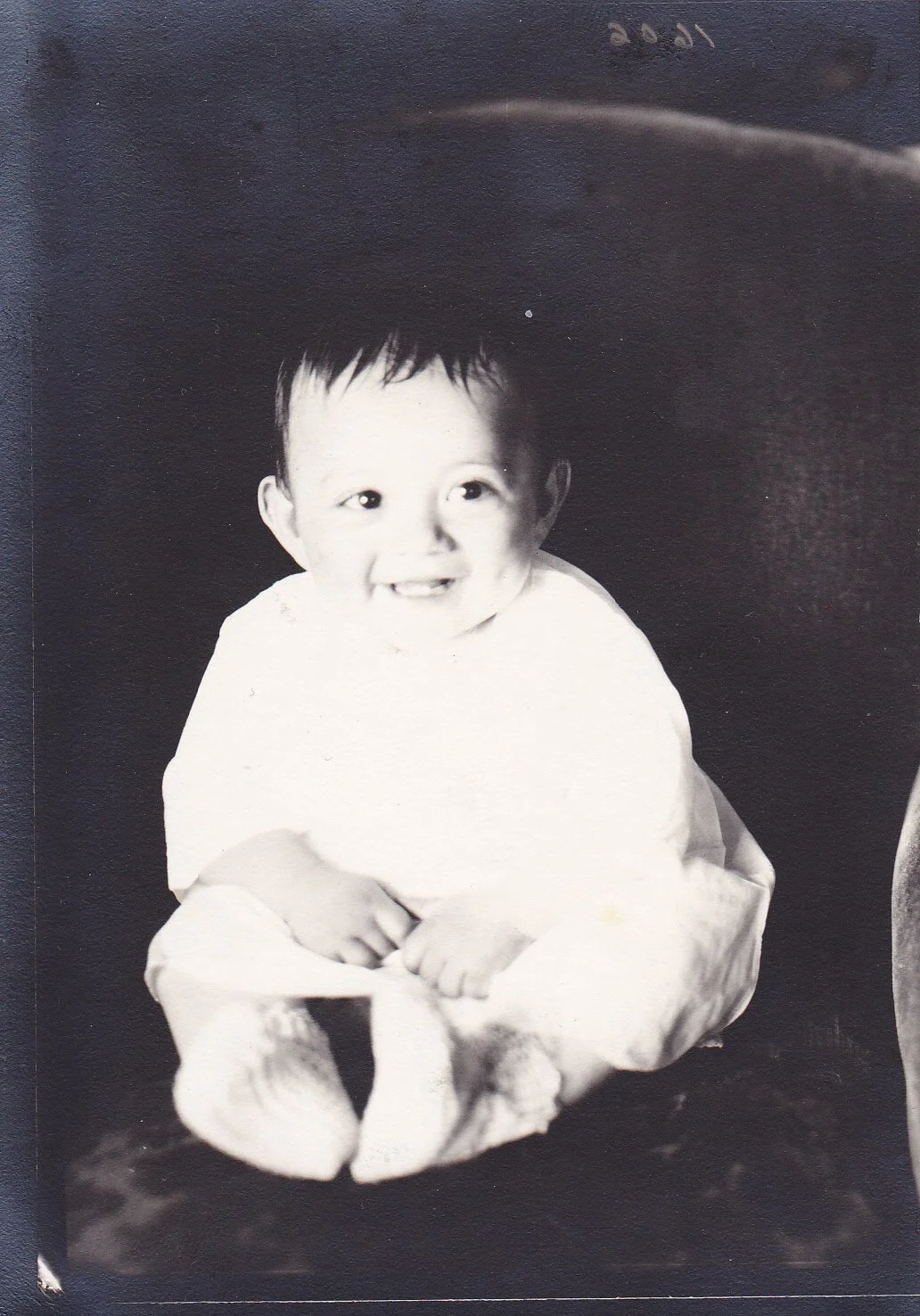

Since I am sharing stories about names, here’s one about my own: I am the first-born of three children in my family. Stories passed down from the time prior to my imminent arrival on this earth included speculation by others as to what the color of my skin would be: would I be yellow, olive, white? Would I have stripes? Should they name me Zebra, rhymes with Deborah? (True story, by the way. Ouch. And thankfully THAT name was ruled out.) My parents came up with the name Rineko, a tribute to my grandfather Rine with the diminutive “–ko” added, essentially naming me “little Rine.” However, it was decreed that Rineko “sounded too Japanese.” The two parts were inverted and I was named Korine.

Rinney Fujiwara (Grandpa Fujiwara)

There are so many stories that I wish I’d had the foresight to ask someone to tell me. No one is alive today who knows the answers to my questions, so some parts of my story are fleshed out with details from old letters and other correspondence, through census and draft records, obituaries, family photos, and memories by relatives. Details differ from sibling to sibling, cousin to cousin, as all the aunts and uncles all had slightly different memories of events.

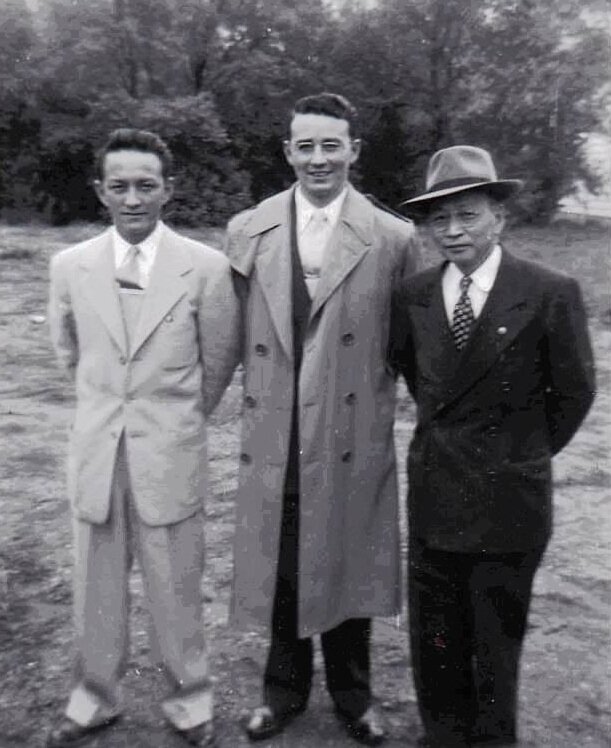

The ship, Tanba-Maru

Through digging around census records and draft registrations, I was able to find the name of the ship my grandfather sailed upon, but family accounts vary as to which port he actually arrived. San Francisco is one city name that was often repeated, as was Seattle. The Tanba-Maru, the ship on which he emigrated, stopped at both ports. An older relative, (though accounts differ as to whether it was his father, his uncle, or his brother) emigrated to the US first and worked in restaurants, and my grandfather later followed him to the US and joined forces with him working in restaurants. Eventually they both went their separate ways.

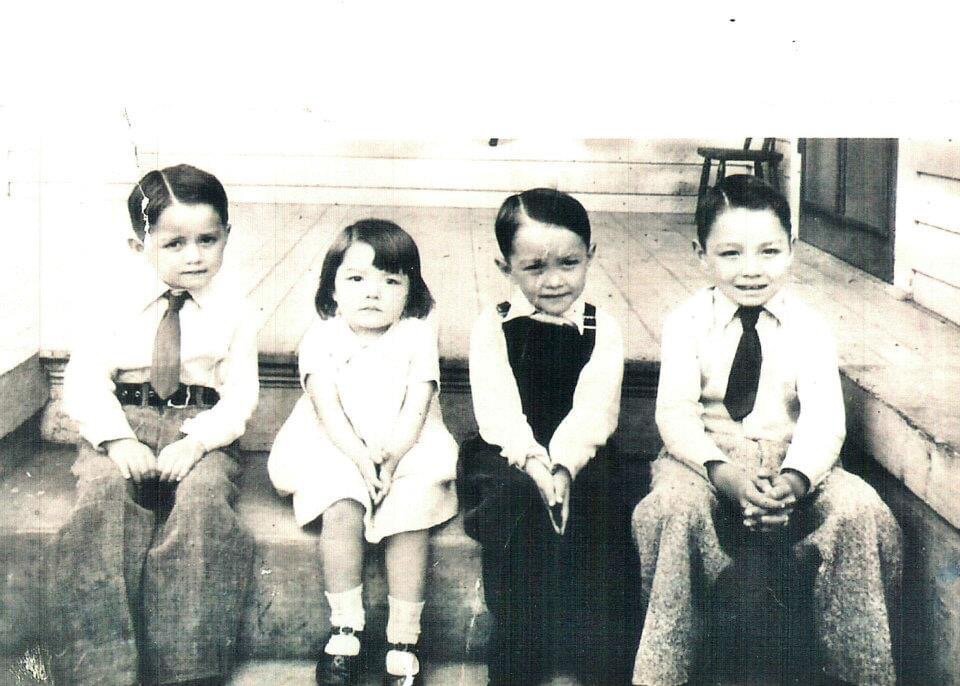

My grandfather traveled west and north, with census records and draft cards showing that he spent some time in Havre, Montana with other Japanese immigrants, and eventually ended up in New Rockford, North Dakota. In New Rockford he owned a restaurant called The Rockford Cafe, where he met and married the woman who eventually became my grandmother. She had three children from a previous marriage (Paul, Grace, Clyde), and together they had four more children: Tayro Rinney (Taro Rine), Huygene K (Huzin Kazuo), my father Karlo Dean (Haruo Jin), and Suye Ann (Sizue Zen).

The details about the treatment of Japanese families in the United States during World War II are well-documented. Had my grandfather stayed in the restaurant business in either Seattle or San Francisco, working with or without his older relative, he would have been sent to an internment camp. Because my grandfather was in North Dakota, he was not relocated to a camp, however, his restaurant was closed and he was detained. After being detained he was sent to work in the fields harvesting sugar beets. My grandmother was left alone with the four younger children and her older daughter. Her two older sons had enlisted and were both killed in the Pacific Theater.

From another recollection of my father:

The wind breaker willows along the Northern Pacific Railroad fill embankment gave us a warming place while we ice skated on the backwash pond of the James River during the thirties. Every winter we put on our ice skates and took them off near the small campfire. This was the starting point on the morning of December 7, 1941 when we skated all the way to Dundas Bridge and back. When we stumbled back up to the railroad tracks and trudged along the quarter mile or so home with wet pant legs from the knees down, the sub-zero temperatures quickly froze the trousers and our legs kept warm. We practically fell through the kitchen door shouting and laughing. Momma was sitting at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee in front of her and a Camel cigarette in her hand. We were surprised to see her because usually on Sunday afternoons she should be working at the restaurant, because that was always a busy time. Mom told us come with her to talk with Daddy at the cafe but we had to go to the basement window and knock on it and call for him. This was strange. “Why couldn’t we just walk in like we always did?” we asked, because the cafe was just kitty corner across the alley. When we kneeled down at the window and Mom called Daddy to the window, we saw two other men behind him. It was then we found out that Daddy had to close the restaurant early because Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and he was in “protective custody” by a government agency with machine guns. We kids asked each other, “What is a Pearl Harbor? And why is Daddy under arrest?” Of course we found out later that our daddy wasn’t “under arrest,” also that all of Daddy’s finances were frozen. We knew what frozen meant to us, but how do they freeze money? We learned what foreclosure meant that day too, it was what all of Daddy’s friendly creditors did on his loans. It also allowed them to seize the restaurant, food, fixtures, dishes, appliances, virtually everything. We went to school on Monday. It was two weeks before we would see Daddy again when he was released and came home.

Empathy and sympathy as I watched my mother’s eyes as she winced in pain for others and lent her comfort expressing to them her strength. We would respond to adapt, and adopt, her adeptness to feel the hurt of others and at the same time give them comfort. In her, I found the one who lived the pain and sufferings in her own life long before and continued to endure through to her death, far too soon. She was a rock of faith, in all her sufferings, never doubting even when her two oldest sons were killed in Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima. How does one adapt to that kind of loss? Anger toward those that cause the pain? Those were the years I really focused on Mom, she showed us acceptance with pain. I learned from her acceptance by forgiving. How could I not forgive? They were killed by the Japanese, and it would have been easy to focus on that factor, except my father was Japanese, so was I. Hurting of the killing of my brothers, and not able to hate the killers, for years I thought they were the same. That contrast worked on me for years until at some point in time I found I wasn’t able to hate anyone no matter what they did. There came a time when I realized I liked all people. I no longer remembered the pain. Maybe now I learned how mom could be so adept at sympathy and empathy for all people. Love.

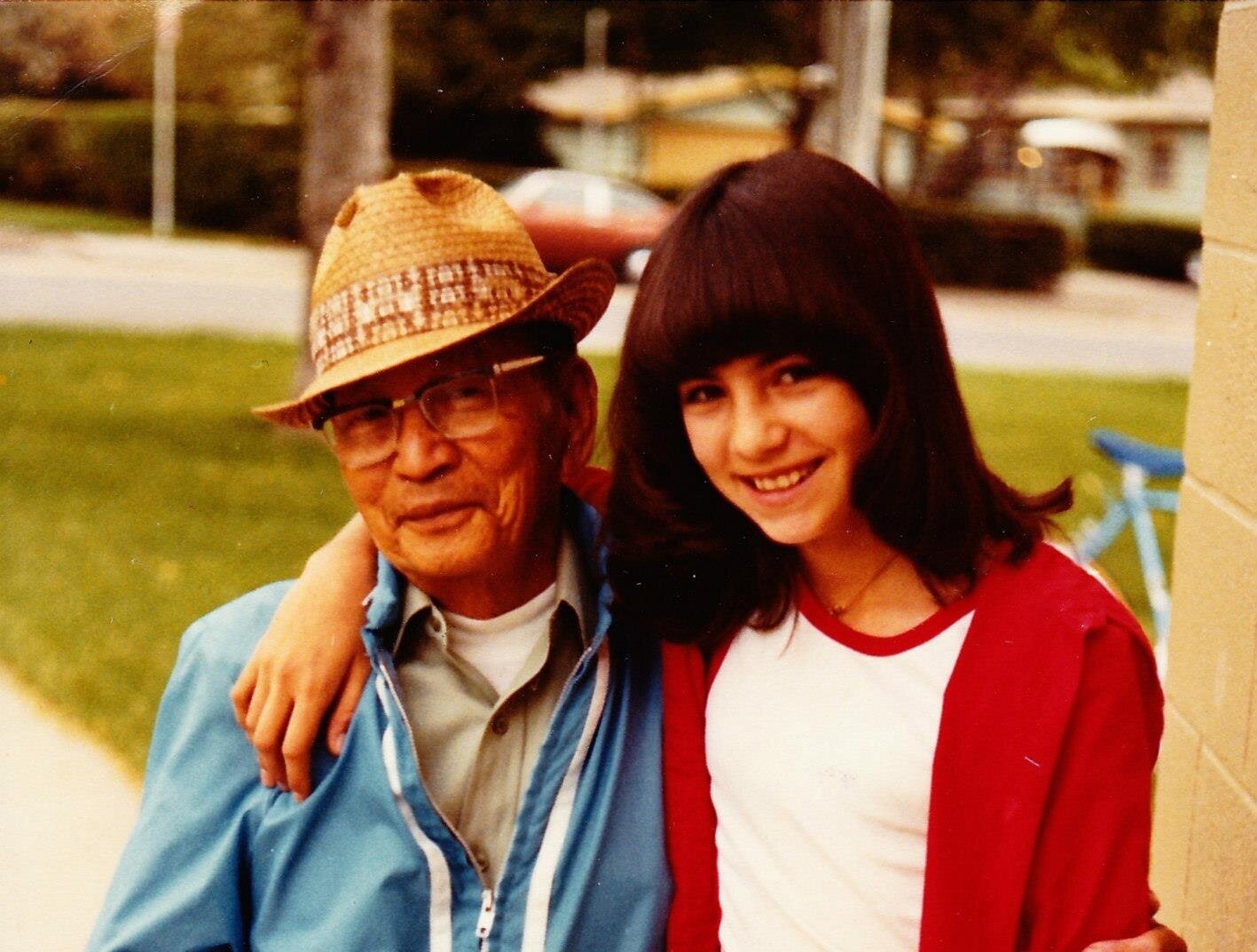

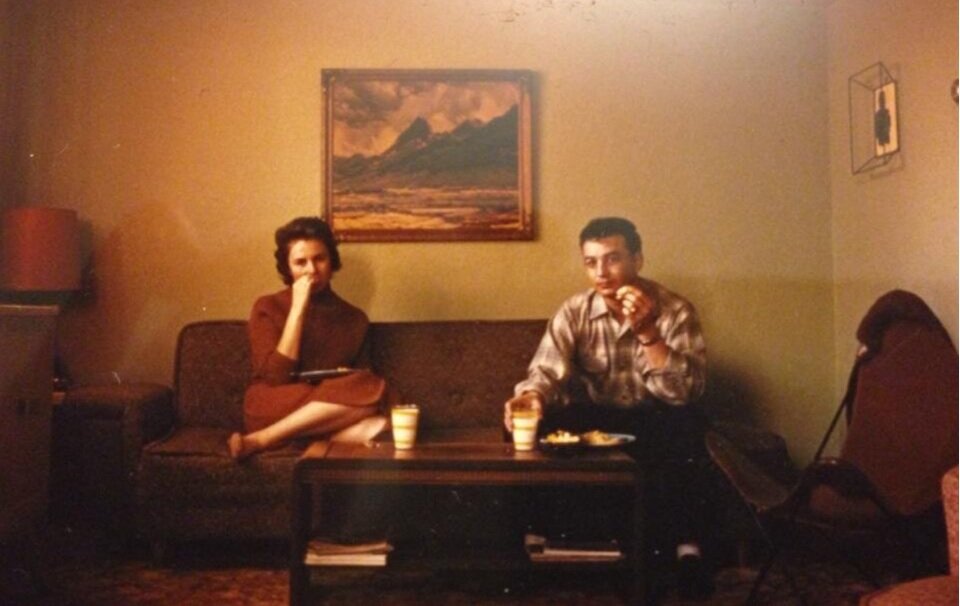

Grandpa Rinney and Korine

I have memories of working in the garden as a child with my grandfather during the summer. He had the most immaculate yard, and we would spend hours deadheading marigolds and saving seeds, watering, weeding, trimming. After I “helped” him, we would walk three blocks from his house down to the pharmacy, (sometimes if I was lucky we stopped at the bakery and got Bismarck pastries, too). The pharmacy had a candy counter, and I would get a red lollipop. On the way there and back, sometimes he would pass people on the sidewalk with a friendly wave. To others, in response to their “Hello, Rine” he would touch the brim of his hat, nod, and quietly respond, “Ah, so,” while continuing to walk. It was much later that I put two and two together that these were the same people who had taken everything from his family during World War II. “Ahhhsssole.” I agree, Grandpa!

Regarding the storyline alternative branch where my grandfather chooses to stay in Japan – one family story, told many times about World War II in Japan regarding my grandfather’s family was of an aunt who had been riding her bicycle on the street just as the bombs were dropped by US forces, and she, along with hundreds of thousands of civilians, was lost.

My grandmother died in 1954. Her oldest daughter Grace stayed in North Dakota, married, and raised a family. My Uncle Tayro went on to become a Major in the Air Force. My Uncle Huygene became a food scientist at Ralston Purina. My Aunt Suye married and raised a family, splitting her time between North Dakota and Illinois. My father attended Minot State Teacher’s College (now Minot State University) and became an artist, and later moved to Billings, Montana, where he had a long career as a commercial artist and a second career as martial arts instructor.

The story of my father sitting down at the piano to try and capture the attention of my mother by playing Debussy’s Clair de Lune is a true one. Though he had good musical instincts and had a terrific ear, my father was never trained in music, let alone piano. He could only fake his way through the first few measures of Debussy before he would have had to start improvising. My mother, also born with fantastic natural musical ability but raised on a tiny ranch in Montana, had likely never heard the Debussy before, but she recognized beautiful music when she heard it. Fortunately for them both (and for me) she responded quickly!

I decided to use thematic motif of the rising then falling 3rds in the opening of the Debussy throughout the music I wrote for my story ~ quite clearly I seem to owe my very existence to Debussy’s Clair de Lune as much as anything else!